Lewis Hine in Lynchburg

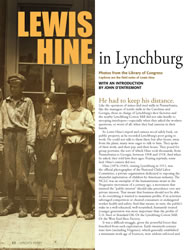

He had to keep his distance. Like the operators of mines and steel mills in Pennsylvania, like the managers of textile mills in the Carolinas and Georgia, those in charge of Lynchburg’s shoe factories and the nearby Lynchburg Cotton Mill did not take kindly to snooping interlopers—especially when they asked the workers questions, or worst of all, when they had cameras in their hands.

So Lewis Hine’s tripod and camera stood safely back, on public property, as he recorded Lynchburg’s poor going to work. He could not talk to them then; but after hours, away from the plant, many were eager to talk to him. They spoke of their work, and their pay, and their hours. They posed for group portraits, the sort of which Hine took thousands, from Pennsylvania to Georgia, between 1908 and 1918. And when he asked, they told him their ages. Fearing reprisals, some lied. Hine’s camera did not.

Hine (1874–1940), visiting Lynchburg in 1911, was the official photographer of the National Child Labor Committee, a private organization dedicated to exposing the shameful exploitation of children by American industry. The NCLC was an exemplar of the humanitarian strain in the Progressive movement of a century ago, a movement that insisted the “public interest” should take precedence over any private interest. That meant that business should not be able to do everything it wanted to maximize profits, if its activities sabotaged competition or cheated consumers or endangered worker health and safety. And that meant, in turn, the public’s stake in a well-educated, well-nourished, humanely treated younger generation was more important than the profits of U.S. Steel or Standard Oil. Or the Lynchburg Cotton Mill. Or the West End Shoe Factory.

Entire article available only in printed version. Lynch's Ferry is on sale at the following Lynchburg locations: Bookshop on the Avenue, Givens Books, Lynchburg Visitors Center, Old City Cemetery, Point of Honor, Market at Main, and Lynch's Ferry office at The Design Group, 1318 Church Street, Lynchburg.

So Lewis Hine’s tripod and camera stood safely back, on public property, as he recorded Lynchburg’s poor going to work. He could not talk to them then; but after hours, away from the plant, many were eager to talk to him. They spoke of their work, and their pay, and their hours. They posed for group portraits, the sort of which Hine took thousands, from Pennsylvania to Georgia, between 1908 and 1918. And when he asked, they told him their ages. Fearing reprisals, some lied. Hine’s camera did not.

Hine (1874–1940), visiting Lynchburg in 1911, was the official photographer of the National Child Labor Committee, a private organization dedicated to exposing the shameful exploitation of children by American industry. The NCLC was an exemplar of the humanitarian strain in the Progressive movement of a century ago, a movement that insisted the “public interest” should take precedence over any private interest. That meant that business should not be able to do everything it wanted to maximize profits, if its activities sabotaged competition or cheated consumers or endangered worker health and safety. And that meant, in turn, the public’s stake in a well-educated, well-nourished, humanely treated younger generation was more important than the profits of U.S. Steel or Standard Oil. Or the Lynchburg Cotton Mill. Or the West End Shoe Factory.

Entire article available only in printed version. Lynch's Ferry is on sale at the following Lynchburg locations: Bookshop on the Avenue, Givens Books, Lynchburg Visitors Center, Old City Cemetery, Point of Honor, Market at Main, and Lynch's Ferry office at The Design Group, 1318 Church Street, Lynchburg.

^ Top

Previous page: Abram Frederick Biggers

Next page: From the Editor

Site Map