Training America’s Youth in “Woodlore, Watersports, and the Mysteries of the Great Outdoorsâ€: Lynchburg-Area Boy Scout Camps in the Twentieth Century

At the turn of the century, following decades of urbanization and mechanization throughout the United States, Ernest Thompson Seton declared that the “whole nation is turning toward the outdoor life, seeking in it the physical regeneration needed for continued national existence.” While it was an overstatement that the “whole nation” was turning to the outdoors, men like Seton and his peer Daniel Carter Beard strongly believed that more Americans needed exposure to the outdoors as a way of re-centering the country’s soul, and both would work to eventually form the Boy Scouts of America in 1910.

As families seeking employment moved from rural areas into cities at an increasing rate in the late nineteenth century, the dynamics of childhood began to change. Male role models left home each day to work in factories, and, for those families living in urban tenements, there was little outdoor work to be done by the boys of the household. These changes led to idle boys roaming neighborhoods seeking any sort of activity, whether positive or not. Seton was fearful that this idleness would lead to a national leadership vacuum as these boys grew into men, but he did not blame the boys, instead saying that the youth of America did not need reforming, but rather “protection from deformation.” To Seton, Beard, and others, only the solitude of the outdoors, whether in a backyard or in the backcountry, could provide the requisite protection of the ill-fated generation while also providing a neutral space in which to “teach boys character in a way that they like to be taught,” in the words of Robert Baden-Powell, author of Scouting for Boys and founder of the Scouting program in the United Kingdom.

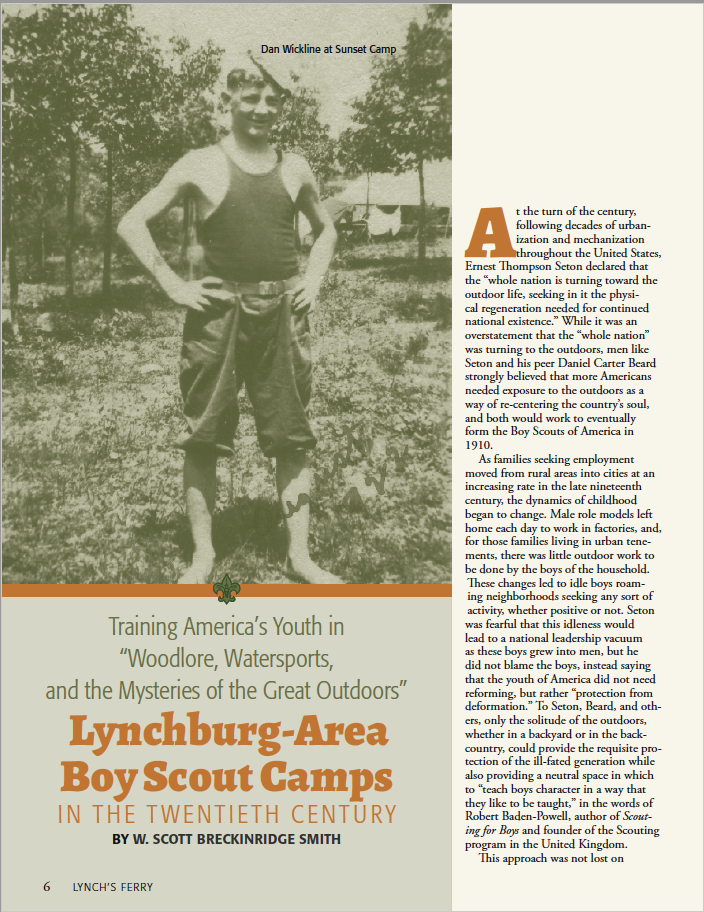

This approach was not lost on twenty-three-year-old Frank Chipman Wood, assistant superintendent of playgrounds in Washington, D.C., where his department led a campaign to encourage children to play in provided spaces rather than on the street. In Washington, he was actively involved in Scouting, serving as assistant commissioner for the city and as director of Camp Archibald Butt on the Chesapeake Bay. Because of this, it is not surprising that he brought the Scouting program with him when he was hired to become the director of athletics for Lynchburg City Schools in the fall of 1913. Within a year, Wood formed Troop 1 and became its first Scout-master.

By early 1920, three Lynchburg troops were operating and two additional units were in formation, necessitating the need for the creation of a local umbrella organization (called a “council” in Scout parlance). In April, the Lynchburg Council of the BSA was officially chartered. The council’s first executive was Adam Jones Himmelsbach (1881–1972), who previously had served as assistant Scout executive of the Chester County Council and director of Camp Lafayette in Pennsylvania.

As families seeking employment moved from rural areas into cities at an increasing rate in the late nineteenth century, the dynamics of childhood began to change. Male role models left home each day to work in factories, and, for those families living in urban tenements, there was little outdoor work to be done by the boys of the household. These changes led to idle boys roaming neighborhoods seeking any sort of activity, whether positive or not. Seton was fearful that this idleness would lead to a national leadership vacuum as these boys grew into men, but he did not blame the boys, instead saying that the youth of America did not need reforming, but rather “protection from deformation.” To Seton, Beard, and others, only the solitude of the outdoors, whether in a backyard or in the backcountry, could provide the requisite protection of the ill-fated generation while also providing a neutral space in which to “teach boys character in a way that they like to be taught,” in the words of Robert Baden-Powell, author of Scouting for Boys and founder of the Scouting program in the United Kingdom.

This approach was not lost on twenty-three-year-old Frank Chipman Wood, assistant superintendent of playgrounds in Washington, D.C., where his department led a campaign to encourage children to play in provided spaces rather than on the street. In Washington, he was actively involved in Scouting, serving as assistant commissioner for the city and as director of Camp Archibald Butt on the Chesapeake Bay. Because of this, it is not surprising that he brought the Scouting program with him when he was hired to become the director of athletics for Lynchburg City Schools in the fall of 1913. Within a year, Wood formed Troop 1 and became its first Scout-master.

By early 1920, three Lynchburg troops were operating and two additional units were in formation, necessitating the need for the creation of a local umbrella organization (called a “council” in Scout parlance). In April, the Lynchburg Council of the BSA was officially chartered. The council’s first executive was Adam Jones Himmelsbach (1881–1972), who previously had served as assistant Scout executive of the Chester County Council and director of Camp Lafayette in Pennsylvania.

^ Top

Previous page: Spring 2018

Next page: Through the Lens of James Thomas Smith: An Archive of Lynchburg’s Black History

Site Map