Through the Lens of James Thomas Smith: An Archive of Lynchburg’s Black History

“Thank God she didn’t throw them out.”

Those were the words of museum volunteer Ann Mitchell remarking on the significance of the Smith Collection, calling it “an archive of Lynchburg’s black history.”

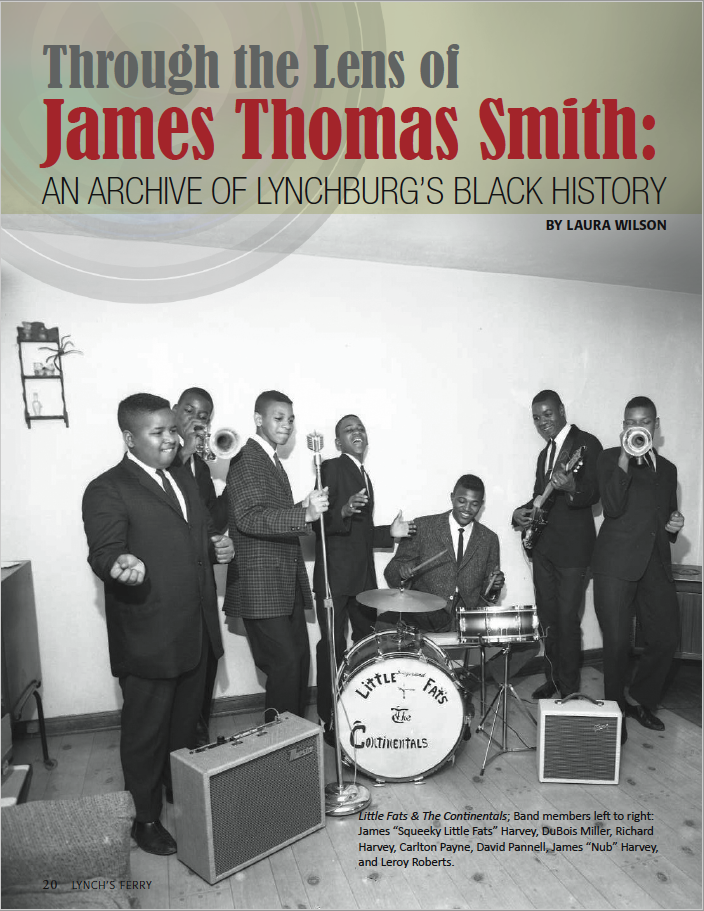

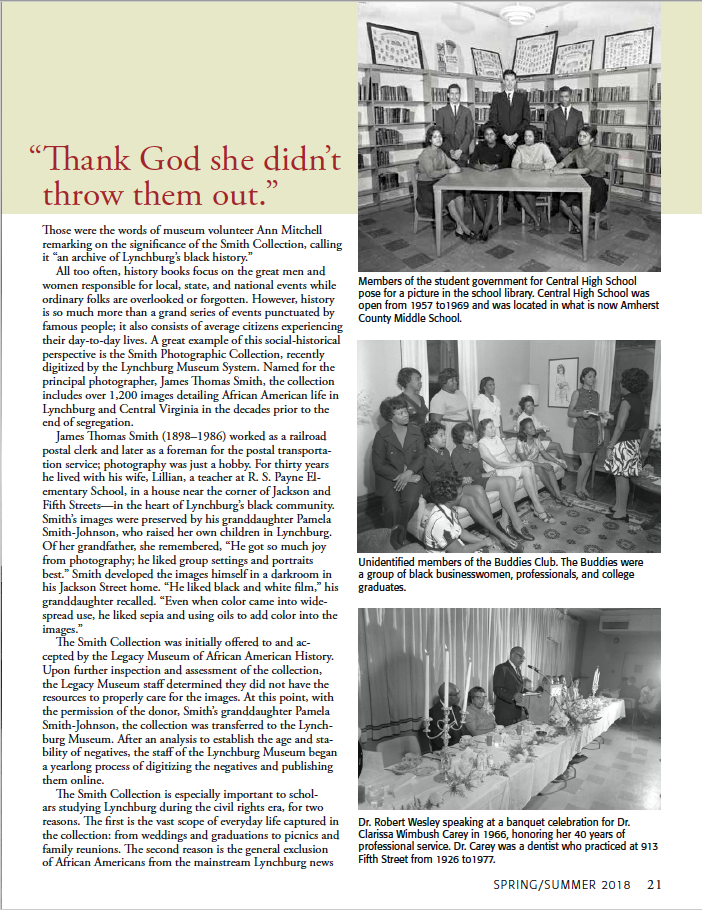

All too often, history books focus on the great men and women responsible for local, state, and national events while ordinary folks are overlooked or forgotten. However, history is so much more than a grand series of events punctuated by famous people; it also consists of average citizens experiencing their day-to-day lives. A great example of this social-historical perspective is the Smith Photographic Collection, recently digitized by the Lynchburg Museum System. Named for the principal photographer, James Thomas Smith, the collection includes over 1,200 images detailing African American life in Lynchburg and Central Virginia in the decades prior to the end of segregation.

James Thomas Smith (1898–1986) worked as a railroad postal clerk and later as a foreman for the postal transportation service; photography was just a hobby. For thirty years he lived with his wife, Lillian, a teacher at R. S. Payne Elementary School, in a house near the corner of Jackson and Fifth Streets—in the heart of Lynchburg’s black community. Smith’s images were preserved by his granddaughter Pamela Smith-Johnson, who raised her own children in Lynchburg. Of her grandfather, she remembered, “He got so much joy from photography; he liked group settings and portraits best.” Smith developed the images himself in a darkroom in his Jackson Street home. “He liked black and white film,” his granddaughter recalled. “Even when color came into widespread use, he liked sepia and using oils to add color into the images.”

The Smith Collection was initially offered to and accepted by the Legacy Museum of African American History. Upon further inspection and assessment of the collection, the Legacy Museum staff determined they did not have the resources to properly care for the images. At this point, with the permission of the donor, Smith’s granddaughter Pamela Smith-Johnson, the collection was transferred to the Lynchburg Museum. After an analysis to establish the age and stability of negatives, the staff of the Lynchburg Museum began a yearlong process of digitizing the negatives and publishing them online.

Those were the words of museum volunteer Ann Mitchell remarking on the significance of the Smith Collection, calling it “an archive of Lynchburg’s black history.”

All too often, history books focus on the great men and women responsible for local, state, and national events while ordinary folks are overlooked or forgotten. However, history is so much more than a grand series of events punctuated by famous people; it also consists of average citizens experiencing their day-to-day lives. A great example of this social-historical perspective is the Smith Photographic Collection, recently digitized by the Lynchburg Museum System. Named for the principal photographer, James Thomas Smith, the collection includes over 1,200 images detailing African American life in Lynchburg and Central Virginia in the decades prior to the end of segregation.

James Thomas Smith (1898–1986) worked as a railroad postal clerk and later as a foreman for the postal transportation service; photography was just a hobby. For thirty years he lived with his wife, Lillian, a teacher at R. S. Payne Elementary School, in a house near the corner of Jackson and Fifth Streets—in the heart of Lynchburg’s black community. Smith’s images were preserved by his granddaughter Pamela Smith-Johnson, who raised her own children in Lynchburg. Of her grandfather, she remembered, “He got so much joy from photography; he liked group settings and portraits best.” Smith developed the images himself in a darkroom in his Jackson Street home. “He liked black and white film,” his granddaughter recalled. “Even when color came into widespread use, he liked sepia and using oils to add color into the images.”

The Smith Collection was initially offered to and accepted by the Legacy Museum of African American History. Upon further inspection and assessment of the collection, the Legacy Museum staff determined they did not have the resources to properly care for the images. At this point, with the permission of the donor, Smith’s granddaughter Pamela Smith-Johnson, the collection was transferred to the Lynchburg Museum. After an analysis to establish the age and stability of negatives, the staff of the Lynchburg Museum began a yearlong process of digitizing the negatives and publishing them online.

^ Top

Previous page: Training America’s Youth in “Woodlore, Watersports, and the Mysteries of the Great Outdoorsâ€: Lynchburg-Area Boy Scout Camps in the Twentieth Century

Next page: The Day I Met MLK

Site Map