One Man’s Outrage: Samuel Miller and the Day the Yankees Came

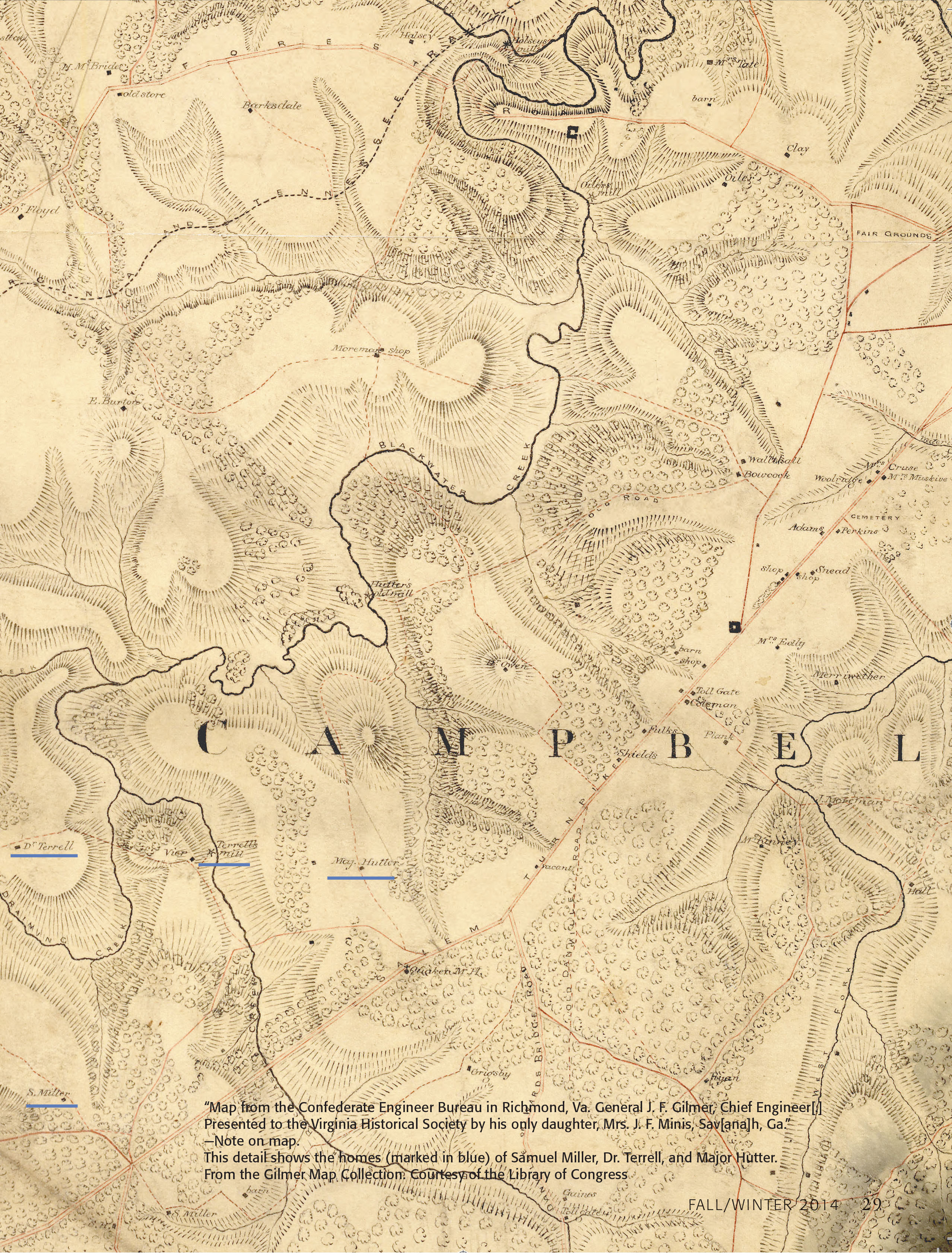

The Battle of Lynchburg, a brief but significant military engagement that occurred west of the 1864 city limits, has been thoroughly chronicled over the years, both in print and more recently, in a very professionally crafted documentary film. With the establishment of the Historic Sandusky Foundation in 2000, a new dimension was added to the preservation of that episode of local history. Although the plight of the Hutter family at Sandusky is well known, their rural neighbor, less than two miles away, had his own confrontation with Union intruders.

Thursday, June 16, 1864 Weary, having been in the saddle for days, a small detachment of Confederate cavalrymen and their exhausted mounts retired northeastward toward Lynchburg along the Salem Turnpike (now US 460, Timberlake Road). Their

mission: warn nearby residents that Federal cavalry, infantry, and artillery were not far behind. Major General David Hunter, commander of the Union Army of West Virginia, was threatening Lynchburg from the west, continuing his campaign through the Shenandoah Valley. Only days earlier, the Virginia Military Institute had been burned. Now, Hunter’s two infantry and two cavalry divisions—18,000 strong—were at New London, some fourteen miles distant. Although vital to the logistical support of General Lee, Lynchburg had been unscathed by three years of war. Now,

the conflict was about to become a very personal event for its citizens. Hunter’s forward elements were expected to reach the city’s outskirts by the following afternoon.

Entire article available only in printed version. Lynch's Ferry is on sale at the following Lynchburg locations: Bookshop on the Avenue, Givens Books, Lynchburg Visitors Center, Old City Cemetery, Point of Honor, Market at Main, and Lynch's Ferry office at The Design Group, 1318 Church Street, Lynchburg.

Thursday, June 16, 1864 Weary, having been in the saddle for days, a small detachment of Confederate cavalrymen and their exhausted mounts retired northeastward toward Lynchburg along the Salem Turnpike (now US 460, Timberlake Road). Their

mission: warn nearby residents that Federal cavalry, infantry, and artillery were not far behind. Major General David Hunter, commander of the Union Army of West Virginia, was threatening Lynchburg from the west, continuing his campaign through the Shenandoah Valley. Only days earlier, the Virginia Military Institute had been burned. Now, Hunter’s two infantry and two cavalry divisions—18,000 strong—were at New London, some fourteen miles distant. Although vital to the logistical support of General Lee, Lynchburg had been unscathed by three years of war. Now,

the conflict was about to become a very personal event for its citizens. Hunter’s forward elements were expected to reach the city’s outskirts by the following afternoon.

Entire article available only in printed version. Lynch's Ferry is on sale at the following Lynchburg locations: Bookshop on the Avenue, Givens Books, Lynchburg Visitors Center, Old City Cemetery, Point of Honor, Market at Main, and Lynch's Ferry office at The Design Group, 1318 Church Street, Lynchburg.

^ Top

Previous page: The Battle of Lynchburg: A Sesquicentennial Look Back

Next page: When Carry Nation, “The Bar Room Smasher,†Came to Lynchburg

Site Map