The Lynchburg Belt Line and the "West End" Depot

by Garland Harper

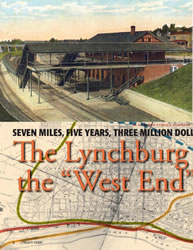

A Lynchburg landmark marks its 100th anniversary this year: Kemper Street Station. The controversial “West End” station was put into commission by the Southern Railway (now a part of Norfolk Southern) on October 31, 1912. Its completion closed the book on a huge line-improvement project.

Lay of the Land

The first railroad rights-of-way were built following the lay of the land to achieve a route as gentle as possible, with as little heavy excavating as possible. Even then, following the lay of the land often resulted in a finished line with many challenging grades and curves. The two railroads that crossed the James River at Lynchburg were originally built in this fashion, and operating trains through the city became more and more difficult as the size of rolling stock and length of trains increased over the years.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, the Southern Railway approached Lynchburg from the north, more or less following Harris Creek from the Winesap area in Amherst County down to the James River. After crossing the James about a half mile above Scott’s Mill dam, the Southern followed the south bank of the river, passing below Point of Honor. Trains crossed Blackwater Creek to enter downtown Lynchburg, passed through a small tunnel under Ninth Street, and continued down the middle of what is now Jefferson Street.

The Norfolk & Western Railway, the other railroad that crossed the James at Lynchburg, entered the city from the west by following Blackwater Creek down to the riverfront. From downtown, the N&W crossed the James onto Percival’s Island where its main railroad yard at the time was located, and then continued across the river into Amherst County.

Downtown Lynchburg had already become a terrible bottleneck for the Southern and the N&W when a third major railroad arrived on the scene. The Chesapeake & Ohio followed the James on its route from Clifton Forge to Richmond. It may not have had the grades its sister railroads had to battle entering and exiting the city, but its traffic through town simply added to congestion woes. All three railroads had to cross at grade at some point near the river’s edge, meaning one railroad’s train would have to stop and let another pass.

The Belt Lines

Both the Southern and the N&W came up with plans to bypass downtown Lynchburg. To make a long story short, the N&W built its bypass, called a “belt line” in railroad terminology, between Forest in Bedford County and Phoebe in eastern Appomattox County. The new line was twenty-three miles in length. Three large trestles had to be built: one over the ravine behind City Stadium where the huge Consolidated Textile Corporation’s mill once stood, one over Possum Creek, and one over Beaver Creek. It was completed in about two years.

The Southern’s belt line around the city was only seven miles in length, stretching north-south from Winesap in Amherst County to Durmid in Campbell County, just beyond the city limits. (Durmid is very close to where the Virginia University of Lynchburg is located.) However, it took considerably longer to build, five years to be exact. A number of factors were to blame, including wrangling with the City of Lynchburg over franchise matters, the lack of construction capital due to the Panic of 1907, and the number and size of the structures that had to be built in that seven miles.

Announcement of the contracts for “Railroad Work at Lynchburg” appeared in a single column on the front page of Lynchburg’s paper, The News, on April 19, 1906. The headline that dominated the paper that day, however, was of a much more terrifying nature, for the great earthquake that devastated San Francisco had occurred the day before.

The announcement called “for the construction of a double-track belt line for a larger part of the way encircling Lynchburg” and went on to explain:

The double track line will be used instead of the line now in use in that city, in order to avoid the heavy grades which it is now necessary to climb to get in and out of that city. The contract also calls for the construction across the James River at Lynchburg of a steel bridge. The two pieces of work are to cost one and a half million dollars.

The “immense” steel bridge, as the newspaper repeatedly described it, was the trestle that still dominates the field of view from Riverside Park and continues to make headlines when some person, unaware of the risk, ventures out upon it with dreadful results.

The Southern had been surveying two possible routes around the city and it is entirely possible that, had things gone the other way, the immense steel bridge across the James might have gone up at a location not too far from where the Carter Glass bridge that carries Business 29 stands today. But instead of choosing the route that would have taken the belt line just north of Madison Heights and across the James east of downtown, the Southern chose the route “through Rivermont, across the suburbs, and via Twelfth Street to Durmid.”

As an interesting aside, the founder and former president of Randolph-Macon Woman’s College, Dr. William Waugh Smith, was beside himself when he learned that a possible routing of this new railroad might bring it close to his institution. According to a March 8, 1906, The News article:

Dr. Smith...discovered that the Southern Ry. in surveying for a better route into the city had planned to come through a ravine which is in close proximity to the big dormitory. Visions of dozens of shrieking, hissing, rumbling trains passing by the college at all hours of the day and night, and gangs of vicious tramps following the great highway between North and South immediately arose and he forthwith approached the officials in charge. He reasoned with them and pointed out the disastrous effects to the college that would result from such a condition, and told them that while he never wished to stand in the way of progress he most strenuously objected to such close quarters with the railroad and suggested another route which would take in part of the college grounds more remote from the buildings.

It is unknown if Dr. Smith’s objections held sway with railroad officials. However, after the belt-line survey to bring the new line in through Rivermont was selected, the new route entered the city a little east of the woman’s college, at a point then known as Water Street (Columbia Avenue today). A November 16, 1906, article in The News indicated that the Southern had acquired all the property it needed to build its belt line:

The right-of-way mentioned has cost the company in round figures the sum of $325,000. Of this amount $250,000 was expended for the right of way through the city and suburbs, while the remainder, above the James River, and below Durmid, cost about $50,000.

Entire article available only in printed version. Lynch's Ferry is on sale at the following Lynchburg locations: Bookshop on the Avenue, The Design Group, Givens Books, Inklings Bookshop, Lynchburg Visitors Center, Macon Bookshop, Old City Cemetery, Point of Honor, and Walgreens on Boonsboro.

Garland R. Harper was born and raised in Lynchburg, growing up on the campus at the Virginia Episcopal School. He’s been watching trains all his life, and has been taking pictures of them since 1964. After graduating from William and Mary in 1975, he went to work for Amtrak as an agent in two stations in West Virginia. He’s been working at Lynchburg’s Kemper Street Station since October 1979.

He’s been married to Peggy for thirty-three years, and they have two sons, Taylor and Stephen. This article is the result of a question he asked himself several years ago: Just how did the local paper report the opening of Kemper Street Station?

A Lynchburg landmark marks its 100th anniversary this year: Kemper Street Station. The controversial “West End” station was put into commission by the Southern Railway (now a part of Norfolk Southern) on October 31, 1912. Its completion closed the book on a huge line-improvement project.

Lay of the Land

The first railroad rights-of-way were built following the lay of the land to achieve a route as gentle as possible, with as little heavy excavating as possible. Even then, following the lay of the land often resulted in a finished line with many challenging grades and curves. The two railroads that crossed the James River at Lynchburg were originally built in this fashion, and operating trains through the city became more and more difficult as the size of rolling stock and length of trains increased over the years.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, the Southern Railway approached Lynchburg from the north, more or less following Harris Creek from the Winesap area in Amherst County down to the James River. After crossing the James about a half mile above Scott’s Mill dam, the Southern followed the south bank of the river, passing below Point of Honor. Trains crossed Blackwater Creek to enter downtown Lynchburg, passed through a small tunnel under Ninth Street, and continued down the middle of what is now Jefferson Street.

The Norfolk & Western Railway, the other railroad that crossed the James at Lynchburg, entered the city from the west by following Blackwater Creek down to the riverfront. From downtown, the N&W crossed the James onto Percival’s Island where its main railroad yard at the time was located, and then continued across the river into Amherst County.

Downtown Lynchburg had already become a terrible bottleneck for the Southern and the N&W when a third major railroad arrived on the scene. The Chesapeake & Ohio followed the James on its route from Clifton Forge to Richmond. It may not have had the grades its sister railroads had to battle entering and exiting the city, but its traffic through town simply added to congestion woes. All three railroads had to cross at grade at some point near the river’s edge, meaning one railroad’s train would have to stop and let another pass.

The Belt Lines

Both the Southern and the N&W came up with plans to bypass downtown Lynchburg. To make a long story short, the N&W built its bypass, called a “belt line” in railroad terminology, between Forest in Bedford County and Phoebe in eastern Appomattox County. The new line was twenty-three miles in length. Three large trestles had to be built: one over the ravine behind City Stadium where the huge Consolidated Textile Corporation’s mill once stood, one over Possum Creek, and one over Beaver Creek. It was completed in about two years.

The Southern’s belt line around the city was only seven miles in length, stretching north-south from Winesap in Amherst County to Durmid in Campbell County, just beyond the city limits. (Durmid is very close to where the Virginia University of Lynchburg is located.) However, it took considerably longer to build, five years to be exact. A number of factors were to blame, including wrangling with the City of Lynchburg over franchise matters, the lack of construction capital due to the Panic of 1907, and the number and size of the structures that had to be built in that seven miles.

Announcement of the contracts for “Railroad Work at Lynchburg” appeared in a single column on the front page of Lynchburg’s paper, The News, on April 19, 1906. The headline that dominated the paper that day, however, was of a much more terrifying nature, for the great earthquake that devastated San Francisco had occurred the day before.

The announcement called “for the construction of a double-track belt line for a larger part of the way encircling Lynchburg” and went on to explain:

The double track line will be used instead of the line now in use in that city, in order to avoid the heavy grades which it is now necessary to climb to get in and out of that city. The contract also calls for the construction across the James River at Lynchburg of a steel bridge. The two pieces of work are to cost one and a half million dollars.

The “immense” steel bridge, as the newspaper repeatedly described it, was the trestle that still dominates the field of view from Riverside Park and continues to make headlines when some person, unaware of the risk, ventures out upon it with dreadful results.

The Southern had been surveying two possible routes around the city and it is entirely possible that, had things gone the other way, the immense steel bridge across the James might have gone up at a location not too far from where the Carter Glass bridge that carries Business 29 stands today. But instead of choosing the route that would have taken the belt line just north of Madison Heights and across the James east of downtown, the Southern chose the route “through Rivermont, across the suburbs, and via Twelfth Street to Durmid.”

As an interesting aside, the founder and former president of Randolph-Macon Woman’s College, Dr. William Waugh Smith, was beside himself when he learned that a possible routing of this new railroad might bring it close to his institution. According to a March 8, 1906, The News article:

Dr. Smith...discovered that the Southern Ry. in surveying for a better route into the city had planned to come through a ravine which is in close proximity to the big dormitory. Visions of dozens of shrieking, hissing, rumbling trains passing by the college at all hours of the day and night, and gangs of vicious tramps following the great highway between North and South immediately arose and he forthwith approached the officials in charge. He reasoned with them and pointed out the disastrous effects to the college that would result from such a condition, and told them that while he never wished to stand in the way of progress he most strenuously objected to such close quarters with the railroad and suggested another route which would take in part of the college grounds more remote from the buildings.

It is unknown if Dr. Smith’s objections held sway with railroad officials. However, after the belt-line survey to bring the new line in through Rivermont was selected, the new route entered the city a little east of the woman’s college, at a point then known as Water Street (Columbia Avenue today). A November 16, 1906, article in The News indicated that the Southern had acquired all the property it needed to build its belt line:

The right-of-way mentioned has cost the company in round figures the sum of $325,000. Of this amount $250,000 was expended for the right of way through the city and suburbs, while the remainder, above the James River, and below Durmid, cost about $50,000.

Entire article available only in printed version. Lynch's Ferry is on sale at the following Lynchburg locations: Bookshop on the Avenue, The Design Group, Givens Books, Inklings Bookshop, Lynchburg Visitors Center, Macon Bookshop, Old City Cemetery, Point of Honor, and Walgreens on Boonsboro.

Garland R. Harper was born and raised in Lynchburg, growing up on the campus at the Virginia Episcopal School. He’s been watching trains all his life, and has been taking pictures of them since 1964. After graduating from William and Mary in 1975, he went to work for Amtrak as an agent in two stations in West Virginia. He’s been working at Lynchburg’s Kemper Street Station since October 1979.

He’s been married to Peggy for thirty-three years, and they have two sons, Taylor and Stephen. This article is the result of a question he asked himself several years ago: Just how did the local paper report the opening of Kemper Street Station?

^ Top

Previous page: Fall 2012

Next page: The J. M. Bell Foundry

Site Map