The Day I Met MLK

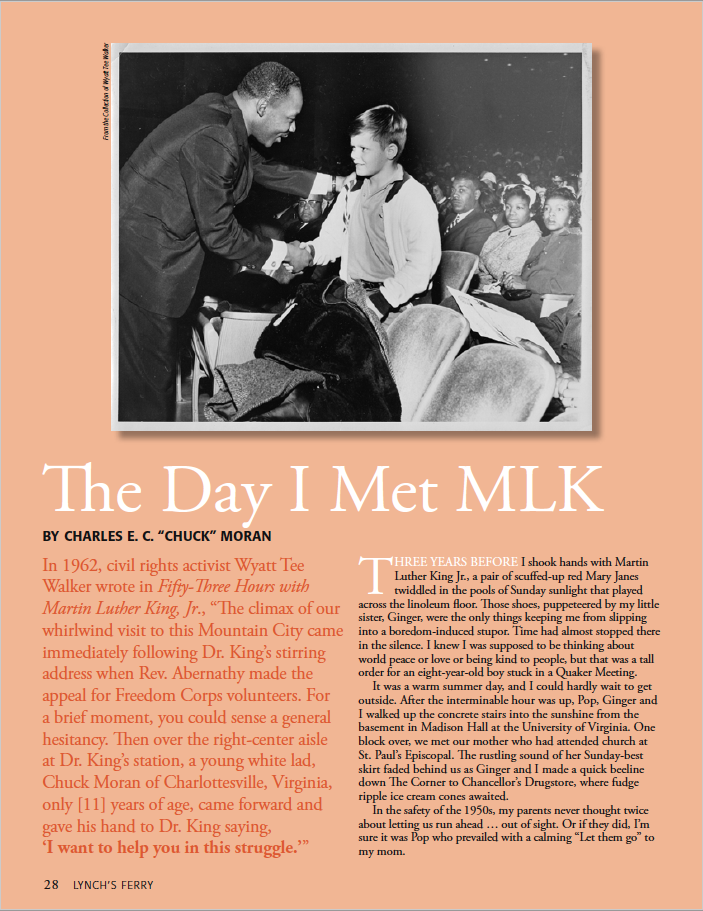

In 1962, civil rights activist Wyatt Tee Walker wrote in Fifty-Three Hours with Martin Luther King, Jr., “The climax of our whirlwind visit to this Mountain City came immediately following Dr. King’s stirring address when Rev. Abernathy made the appeal for Freedom Corps volunteers. For a brief moment, you could sense a general hesitancy. Then over the right-center aisle at Dr. King’s station, a young white lad, Chuck Moran of Charlottesville, Virginia, only [11] years of age, came forward and gave his hand to Dr. King saying, ‘I want to help you in this struggle.’”

Three years before I shook hands with Martin Luther King Jr., a pair of scuffed-up red Mary Janes twiddled in the pools of Sunday sunlight that played across the linoleum floor. Those shoes, puppeteered by my little sister, Ginger, were the only things keeping me from slipping into a boredom-induced stupor. Time had almost stopped there in the silence. I knew I was supposed to be thinking about world peace or love or being kind to people, but that was a tall order for an eight-year-old boy stuck in a Quaker Meeting.

It was a warm summer day, and I could hardly wait to get outside. After the interminable hour was up, Pop, Ginger and I walked up the concrete stairs into the sunshine from the basement in Madison Hall at the University of Virginia. One block over, we met our mother who had attended church at St. Paul’s Episcopal. The rustling sound of her Sunday-best skirt faded behind us as Ginger and I made a quick beeline down The Corner to Chancellor’s Drugstore, where fudge ripple ice cream cones awaited.

In the safety of the 1950s, my parents never thought twice about letting us run ahead … out of sight. Or if they did, I’m sure it was Pop who prevailed with a calming “Let them go” to my mom.

It was late August 1958. I had two years at Venable Elementary School under my belt. The ritual loomed: sharpened pencils in a new plastic box. Maybe a new ruler and always the heavy textbooks that we would wrap in flattened Safeway grocery store bags. A new backpack was not in the budget.

School was about to start when my folks announced some bewildering news. They were saying something about having to go to school, to enter the vaunted third grade, in some lady’s basement. Something about how the city schools were closed — my Venable Elementary was closed, shuttered because Negro kids weren’t going to be allowed to go to school with us white kids. For the fall of that year and into the spring of the next, we inhabited Mrs. Wilson’s basement. Lessons, recess, lunch, nap, home, repeat.

There was a lot I didn’t know or understand at the time — how the grownups were acting out what we now see as an overt and dying vestige of racism, how the next years would be filled with demonstrations and clashes, how many people would not feel safe for a while.

U.S. Senator Harry F. Byrd Sr., who firmly controlled Virginia politics, vehemently opposed integrating public schools despite the Brown v. Board of Education decision handed down by the United States Supreme Court in 1954. Byrd instituted Massive Resistance, a series of laws designed to maintain segregated public schools. Our Charlottesville public schools were seized and closed. Massive Resistance was soon struck down and a few courageous black students began to integrate the schools the following spring.

Three years before I shook hands with Martin Luther King Jr., a pair of scuffed-up red Mary Janes twiddled in the pools of Sunday sunlight that played across the linoleum floor. Those shoes, puppeteered by my little sister, Ginger, were the only things keeping me from slipping into a boredom-induced stupor. Time had almost stopped there in the silence. I knew I was supposed to be thinking about world peace or love or being kind to people, but that was a tall order for an eight-year-old boy stuck in a Quaker Meeting.

It was a warm summer day, and I could hardly wait to get outside. After the interminable hour was up, Pop, Ginger and I walked up the concrete stairs into the sunshine from the basement in Madison Hall at the University of Virginia. One block over, we met our mother who had attended church at St. Paul’s Episcopal. The rustling sound of her Sunday-best skirt faded behind us as Ginger and I made a quick beeline down The Corner to Chancellor’s Drugstore, where fudge ripple ice cream cones awaited.

In the safety of the 1950s, my parents never thought twice about letting us run ahead … out of sight. Or if they did, I’m sure it was Pop who prevailed with a calming “Let them go” to my mom.

It was late August 1958. I had two years at Venable Elementary School under my belt. The ritual loomed: sharpened pencils in a new plastic box. Maybe a new ruler and always the heavy textbooks that we would wrap in flattened Safeway grocery store bags. A new backpack was not in the budget.

School was about to start when my folks announced some bewildering news. They were saying something about having to go to school, to enter the vaunted third grade, in some lady’s basement. Something about how the city schools were closed — my Venable Elementary was closed, shuttered because Negro kids weren’t going to be allowed to go to school with us white kids. For the fall of that year and into the spring of the next, we inhabited Mrs. Wilson’s basement. Lessons, recess, lunch, nap, home, repeat.

There was a lot I didn’t know or understand at the time — how the grownups were acting out what we now see as an overt and dying vestige of racism, how the next years would be filled with demonstrations and clashes, how many people would not feel safe for a while.

U.S. Senator Harry F. Byrd Sr., who firmly controlled Virginia politics, vehemently opposed integrating public schools despite the Brown v. Board of Education decision handed down by the United States Supreme Court in 1954. Byrd instituted Massive Resistance, a series of laws designed to maintain segregated public schools. Our Charlottesville public schools were seized and closed. Massive Resistance was soon struck down and a few courageous black students began to integrate the schools the following spring.

^ Top

Previous page: Through the Lens of James Thomas Smith: An Archive of Lynchburg’s Black History

Next page: The 1917 Lynchburg “Shoemakersâ€

Site Map